Twentieth Century Tour

Huckleberry Point, New Year’s Eve 1895 - the start of a new era. That was the day the Hamilton Blast Furnace Company’s new Blast Furnace “A” was fired up. Over the next 50 years, much of the East End changed from farmland, fields, forests and marsh into heavy industry and workers’ housing. The colossal mills of Stelco, Dofasco and many other companies shaped Hamilton and its workforce. This is the story of the making of the 20th century industrial city.

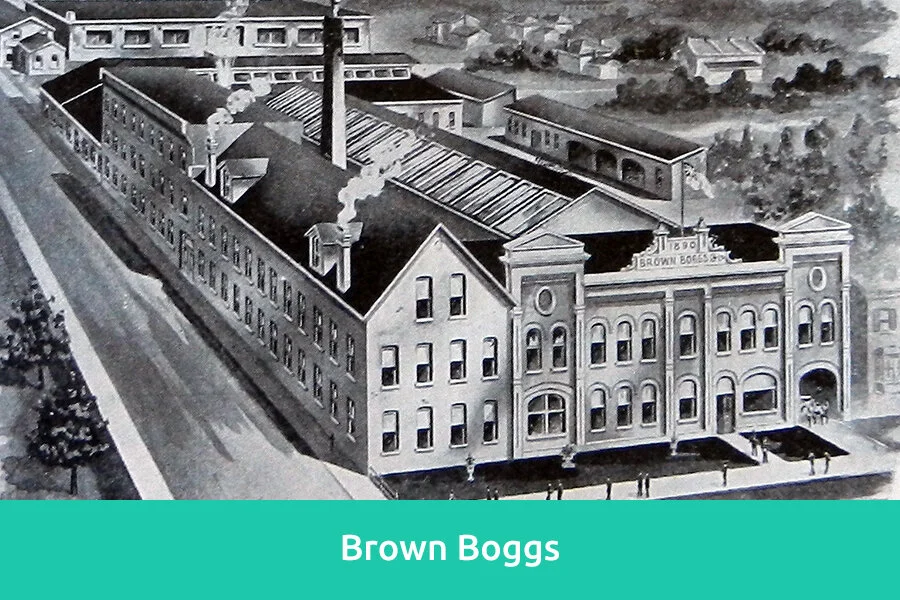

Some East End workplaces were homegrown enterprises: the Hamilton Blast Furnace Company, the Hamilton Bridge Company. Many others were American branch plants set up in Canada to avoid paying high import tariffs. The largest of these firms were Canadian Westinghouse and International Harvester. By 1920, Hamilton had attracted nearly 100 American branch plants.

These new factories looked different. They were massive compared with the 19th century factories downtown. The introduction of electricity brought architectural freedom. These new buildings did not require the shafting and belting of the 19th century steam-powered plants. To increase visibility and ventilation on the shopfloor, architects often used large windows and skylights in their modern plant designs. New building technologies, such as reinforced concrete and structural steel, made these improvements possible.

Read more +

Inside these sprawling plants a second Industrial Revolution was underway. Complex new machinery was introduced. Supervision was close and the pace of work was fast. Production often went around the clock. Shift work became the norm.

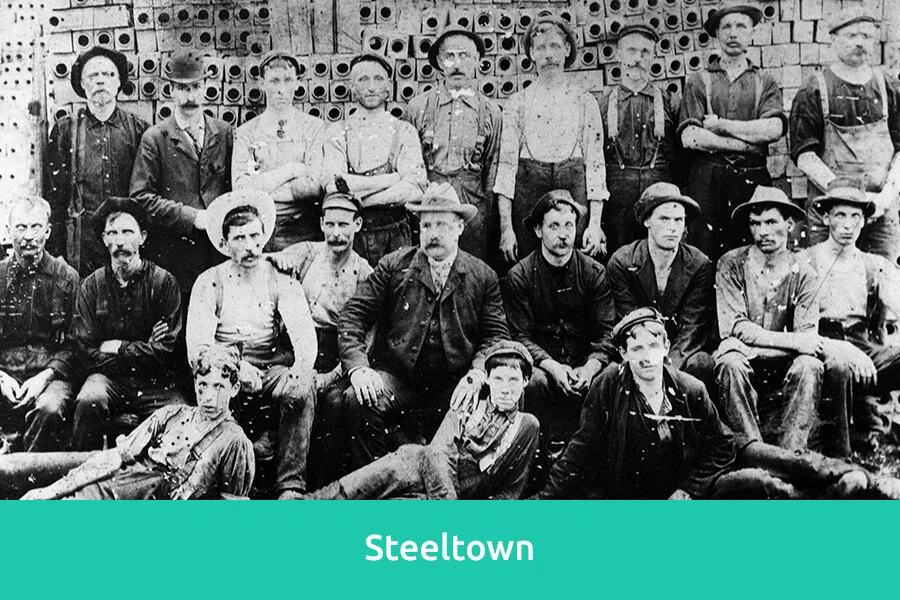

Employers brought a new workforce to these new plants. There was still room for skilled craftsmen, like the British workers so important to Hamilton in the 19th century, but there were far more semi-skilled and unskilled male workers on the shopfloor. Many of them were recent immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Women also found work, especially in the city’s new textile industry. By the 1940s, workers at many East End plants had organized themselves into strong industrial unions. Many of these unions were affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) south of the border. In 1946, workers from the local steel, rubber and electrical industries won a major strike that established industrial unionism in the city.

The city’s first suburbs took shape around these plants. New immigrants from Italy, Armenia, Poland, the Ukraine and other countries rented, built or purchased homes here. Working families used their limited resources to turn these new subdivisions into neighbourhoods. They relied on each other to get through tough times. The stores, churches, community halls and other institutions near the corner of Barton Street East and Sherman Avenue reflected the multi-ethnic character of this new community. Ottawa Street became the city’s second downtown.

Barely twenty years after the blowing in of the first blast furnace and the East End of Hamilton was changed forever. In the shadow of these fiery new mills, thousands of people had to come to live and work. The city proudly billed itself Canada’s “manufacturing metropolis.”

World War II transformed Hamilton industry, erasing the long decade of the Great Depression almost overnight. Local factories retooled for war production and scrambled to increase their productive capacity. Orders poured in for everything from tents and uniforms to armaments and shells.

A new workforce was assembled after thousands of local male factory workers enlisted in the armed forces. “Rosie the Riveter” became a common site on the shopfloor, as women were recruited into heavy industrial jobs that had been the traditional preserve of men. The government provided subsidized day care for mothers working in war industries. Men and women flooded in from out of town to perform war work. Many of them lived in barracks and housing that were hurriedly erected by government contractors.

These men and women put in long hours and worked hard to help their fellow citizens fighting for democracy overseas. Once victory was in sight, they began to fight for industrial democracy at home. The introduction of collective bargaining legislation helped unions in many Hamilton plants win their first contracts before the end of the war. A series of strikes in 1946 helped nail down these wartime gains.