East End Tour

Walking a picket line can be a lonely experience. But in the late summer of 1946, Hamilton’s strikers had lots of company. Workers from across the city joined the picket lines at several major firms. Most importantly, working people throughout the East End reached out to help the steelworkers win the famous “Battle of Stelco.”

It was a time of significant change. Two different trends had emerged in the large, new suburban area on the east side of the city: corporations had opened huge factories in the early 1900s that dominated the work lives of thousands of the area’s residents. Yet up and down the streets of the East End, neighbourhoods of working people grew and thrived. Their residents came from many different backgrounds and spoke different languages. But they had built up vibrant communities that, by 1946, were ready to stand up to the big corporations.

This tour takes you along the streets where weary steelworkers trudged home from a 12-hour day on the job, where women attended to their families and their daily chores, where immigrants gathered on street corners to catch up on the news from back home, where union organizers addressed crowds, where children played and where strikers marched. It takes you through neighbourhoods with long histories and rich traditions of singing, dancing, praying, debating, socializing and organizing. Beneath the smokestacks, you will find the Workers’ City.

We think of today’s suburbs as places where people live in neat rows of lookalike houses, far from the hustle and bustle of work. In the early 1900s, however, the suburbs brought work and home closer together. Many suburbs began when big companies set up factories on cheap land at the edge of the city. Neighbourhoods and shopping districts then grew up around these workplaces. This is the story of Hamilton’s East End.

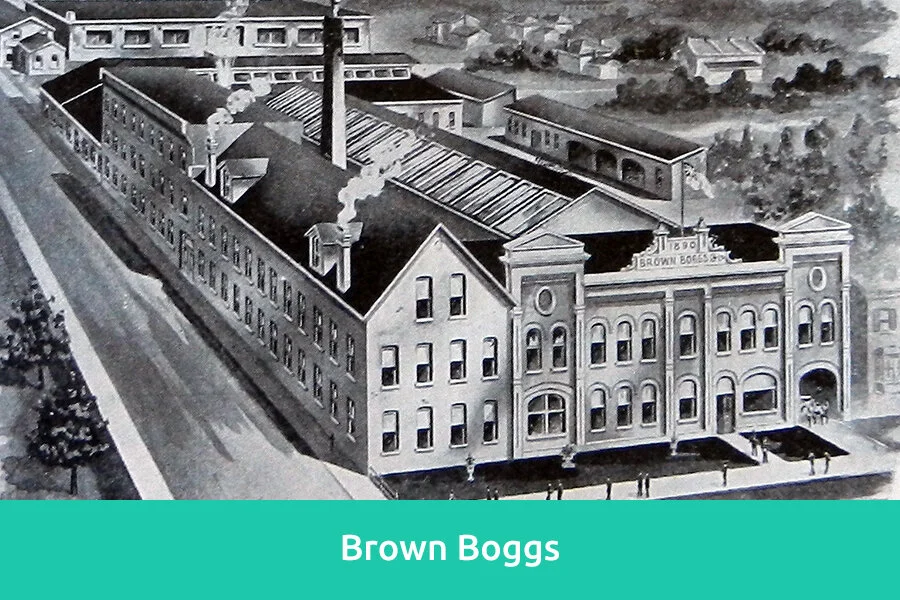

In December 1895, the Hamilton Blast Furnace Company “blew in” its first furnace on farm land northeast of the city. The company grew and merged with other companies until 1910, when it became the new Steel Company of Canada (Stelco), a huge corporation with factories in several cities. By this point, local businessmen and city officials had coaxed other large firms to set up nearby. The biggest of these were International Harvester and Canadian Westinghouse, both branch plants of American corporations. There were a few textile plants, too, but the East End was mainly the new centre of Hamilton’s heavy industry. Here, workers made a wide range of iron and steel products.

Read more +

The time clock: a symbol of the new industrial age

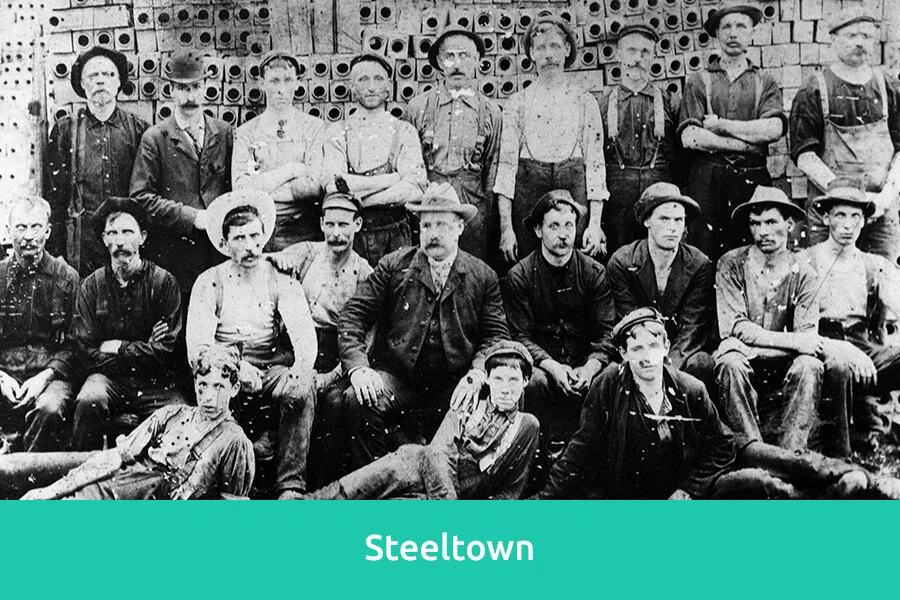

Inside these huge factories, a second Industrial Revolution was soon under way. Workers encountered complex machinery, closer supervision and a general speed-up of work. The symbol of this new industrial age was the time clock. There were more jobs for women in some of the new plants, especially in the knitting mills. In the large metalworking firms, employers began hiring male immigrants from Italy, Poland and other parts of southern and eastern Europe for heavy, hot and poorly paid labouring jobs.

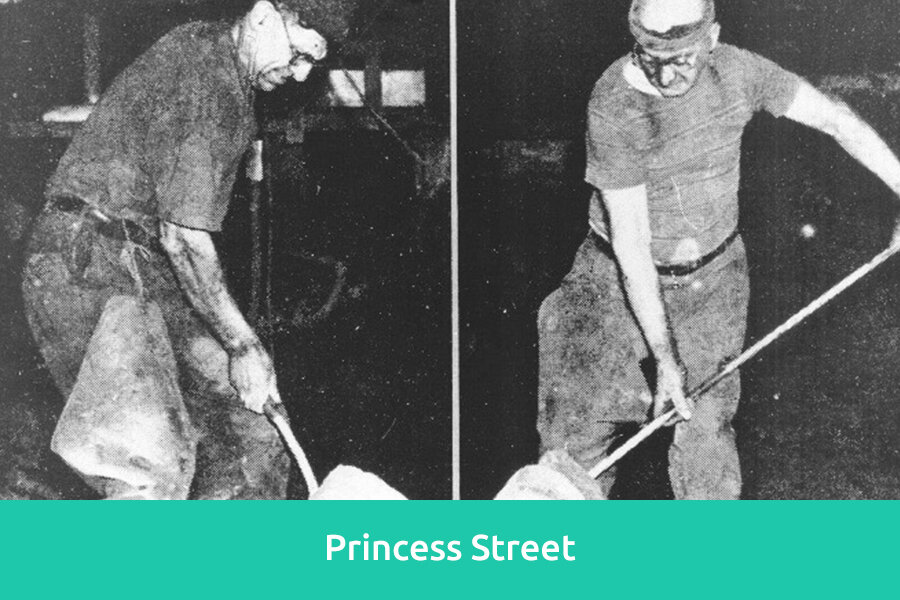

Work in all of these plants was hard. Men and women were on the job 10 hours a day, five-and-a-half or six days a week. At Stelco, the men at the blast furnaces and rolling mills sweated through 12-hour days until 1930. The intense heat, dense smoke and deafening noise increased the danger to workers. Accident rates were astonishingly high.

Daily life was an adventure

After the whistle blew at the end of the day, workers might drop into a local tavern with their workmates — that is, until prohibition turned off the tap in 1916. Then they would head to their homes, which were built on farmland south of the new factories. In the early 1900s, contractors put up small, affordable housing where working-class families could live and keep a small garden and perhaps a few chickens. Many workingmen threw up simple shacks themselves, until they could build something more substantial.

Daily life was an adventure for the early residents of the East End. There were no paved roads, sidewalks or other services. Women had no fancy appliances, and they struggled to make ends meet on the pooled wages of family members. Their ingenuity was essential during the many years of economic depression between the World Wars, especially the 1930s. Employment was irregular, and most working-class families lived with persistent insecurity.

Working families faced their troubles together. Neighbourhoods had grown up in the East End with grocery stores, taverns, churches, community halls and much more. Each neighbourhood was slightly different. Immigrants from the same ethnic group tended to cluster together — English, Italian, Armenian and so on. But more than one group of Europeans often shared the same block. Many of the newcomers were men who had left their families behind and planned to return home with their earnings. They crowded into boardinghouses run by their fellow countrymen on streets close to the big factories. Gradually, they began to blend their old-world customs with their new experiences, and they talked about the harshness and indignities they faced.

Bastions of anti-unionism

By the 1920s, some of the larger companies provided a few benefits for their workers — pensions, life insurance, sports programs and so on. But these gestures were not enough for many workers. Some skilled workers in these plants formed their own craft unions before World War I, and even went on strike. Some groups of immigrant labourers managed to squeeze small wage increases out of their bosses with spontaneous strikes, but no permanent union organization came out of these confrontations. The end of World War I brought a new flurry of organizing, this time involving some industrial unions that included all workers in a plant. Few of these unions survived, however. For most of the years between the wars, Hamilton’s East End factories were bastions of anti-unionism.

For much of this period, however, East Hamilton sent independent labour candidates to the Ontario legislature to fight for their cause. From 1906 to 1919, the venerable stovemounter Allan Studholme was the only labour spokesman in the House. From 1919 to 1923, plumber George Halcrow sat on the government benches in a United Farmers of Ontario (UFO)–Labour coalition. And, from 1934 to 1937, Sam Lawrence, a stonecutter and long-time municipal politician, was the lone member of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). Labour aldermen were also regularly re-elected in the East End, and in 1931 Humphrey Mitchell began a four-year term in the federal Parliament.

The victories of Mitchell and Lawrence showed how deeply the Great Depression affected those living in the East End. Protests by unemployed workers erupted into angry demonstrations in the early 1930s. Workers in some textile plants and in the sheet mill at Stelco marched out on strike. But these were bad times for organizing. Most workers clung fearfully to their jobs and simply tried to survive.

An industrial truce

World War II changed all of this. Workers had more regular jobs, unemployment was a thing of the past and the threat of poverty faded. Union organizers began to get a much more sympathetic ear, and by 1943 they had signed up thousands of Hamiltonians. Workers responded to the appeal for “industrial democracy” at home, in keeping with the war for democracy overseas. In the 1943 provincial election, they once again rejected the mainstream parties and sent labour men to the legislature under the banner of the CCF. Herbert O’Conner, a worker at International Harvester, took the East Hamilton seat. Later that year, the CCF’s Sam Lawrence was elected mayor, along with two CCF aldermen.

Employers fought back. They refused to recognize unions and began to organize company unions instead. They also opposed provincial and federal legislation that would allow union recognition and compulsory collective bargaining. But politicians saw that industrial conflict could get out of control unless it was directed through formal channels. So the new labour legislation stood and, by the end of the war, most of the major East End employers were forced to accept the unions in their plants. Yet how long would this industrial truce last?

The big showdown

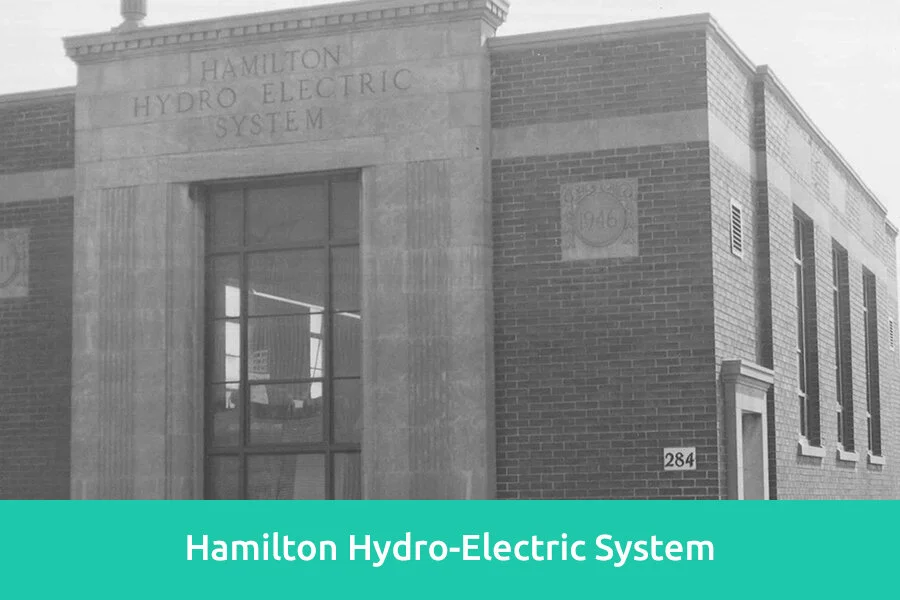

1946 brought the big showdown. Workers and veterans were determined not to let the clock be turned back. By the summer of that year, Firestone and Westinghouse workers were on strike, and all eyes were on Stelco, where negotiations had bogged down. The issues were higher wages, a 40-hour week and the check-off of union dues. On July 15, the “Battle of Stelco” began. The company organized a non-union workforce and gave them food, accommodation and entertainment inside the plant. The union put up a militant picket line outside the gates and kept the plant under siege for 81 days. Mayor Lawrence refused to call in the police to end the blockade. The union also ran a boat in the harbour to head off company suppliers, and dropped leaflets into the plant from an aircraft.

The working people of East Hamilton soon showed how important this strike was to them. Support poured in from East End neighbourhoods. Friends and neighbours from other plants joined the picket line. This was the struggle of a whole community.

In the end, the steelworkers and other strikers won most of their demands. Old-timers in the East End will still tell you what a difference it made to be able to negotiate over wages and at least some working conditions, and to have a grievance system in place. Workers in mass production gained a higher standard of living and a little more dignity on the job. The workers of East Hamilton had led the way in making their city not just a lunch-bucket town, but a union town.