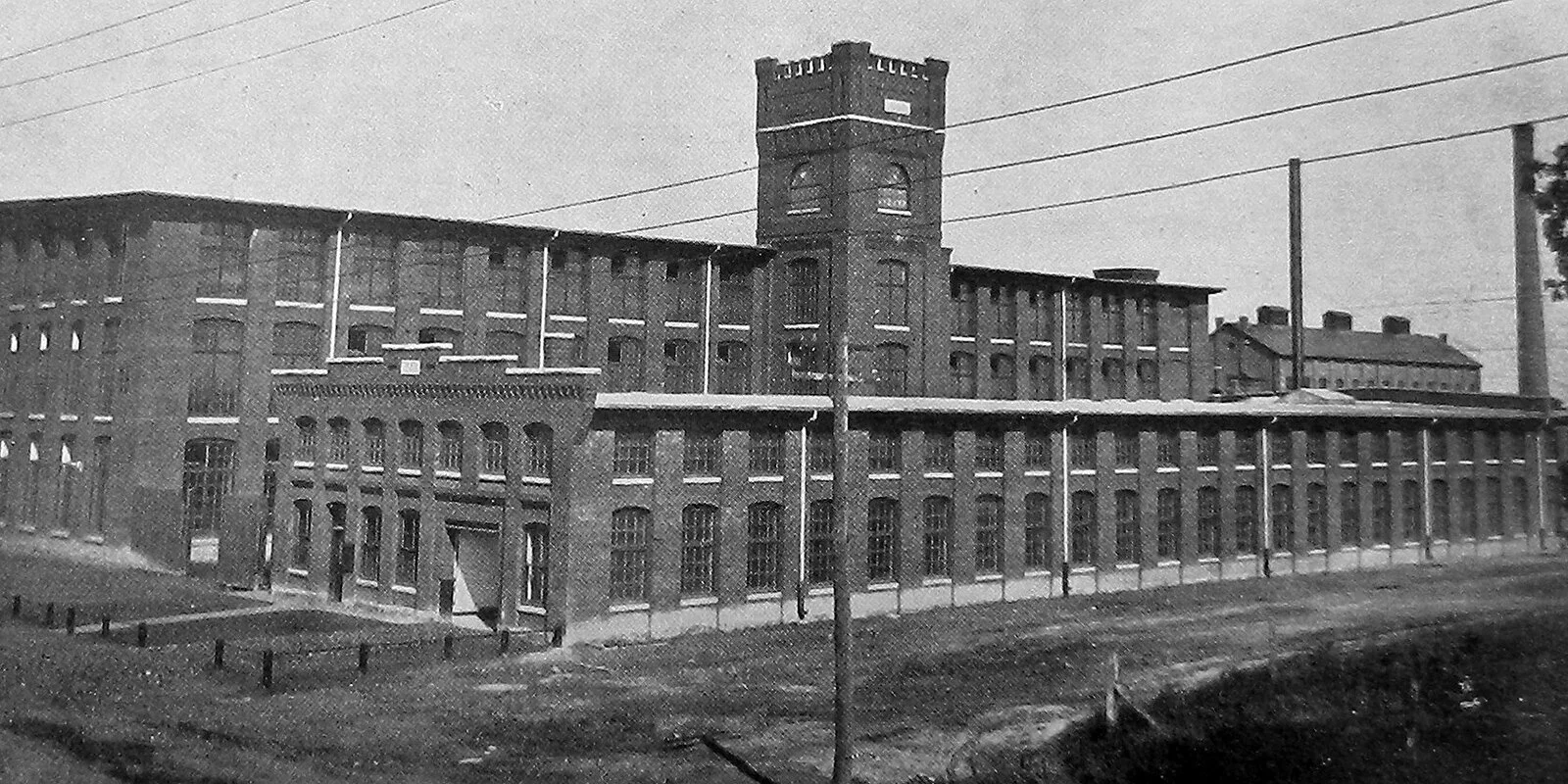

Imperial Cotton Company Ltd.

East side of Sherman Avenue North between Landsdowne Street and Biggar Avenue

Workers in this plant laboured over giant looms and spinning and carding machines to produce heavy cotton duck for sails, mechanical belting for power transmission, railway car roofing, awnings and other products. The plant was opened in 1900 by James M. Young and his associates at the Hamilton Cotton Company. At times, the firm employed more than 300 workers, many of them women. This plant shut down in 1958. The buildings that remain form one of the most complete historic textile mill complexes in the province. Shortly after the turn of the 21st century, large sections of the complex were repurposed as an art space.

The elegant three-storey brick masonry main building, with its medieval-style water tower, housed the bulk of the machinery. An adjoining two-storey building was used for finishing. The carpentry and machine shops were set up in another two-storey section of the plant.

A group of New York capitalists took ownership of the plant soon after it opened, making it the first textile plant in the city to be controlled by American interests — the International Cotton Duck Company of New York City. In 1924, the company amalgamated with another mill in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, creating the Cosmos-Imperial Cotton Company.

The new plant boasted the latest technology. Its 130 looms, 9,000 spindles and 54 carding machines were imported from Britain and the United States. The whole operation was driven entirely by electricity. Power was generated in the factory’s own steam plant.

In 1902, some of the founders of Imperial Cotton started the smaller Dominion Belting Company next door. It produced cotton duck belting for belt-driven machinery. This company closed in the late 1920s, after electrical power made this power-transmission process obsolete.

Like many other workers in this industry, Imperial mill operatives found it hard to unionize. They walked out in May 1910 in protest against a 10 per cent wage cut. The strike lasted a week and involved both male and female employees. The strikers made plans to join the United Textile Workers Union. But the plant reopened and the strikers were back at work the following week. One strike leader attributed this failure to inexperience and the lack of a strike fund.

Management at Imperial Mills used a variety of strategies to appease workers and divert unionism. They softened the bite of technical improvements and work reorganization in the 1920s by introducing programs to win employees’ favour. Workers received financial incentives in the form of group life insurance, pay advances, company-assisted savings plans and home financing. A cafeteria installed in 1920 added comfort to the workplace. Here, workers joined in noon-hour sing-alongs led by Miss Winnifred Parker of the local YWCA. The company also arranged with the YWCA for their female employees to take swimming lessons, play indoor baseball and other games, and go to dances. A company magazine, The Fabricator, featured pictures of workers and reports on all these new programs.

Management also won the support of workers by including them in company schemes to increase productivity. In its monthly “modern production class,” ambitious employees were taught how to make more efficient use of their time and minimize waste. Experts from the Cotton Research Company of Boston were brought in to show how scientific analysis could “effect very larger improvements and economies.” This resulted in a thorough reorganization of the weave room. Plant Superintendent A.F. Knight posted waste-percentage charts in every department. His hope was that employees would “make it a point to become interested in the matter of waste and see if we can’t make Imperial stand out as a leader in the small amount of preventable manufacturing waste.” The outcome of these employee incentive programs was proudly announced in the December 1922 issues of The Fabricator: New management techniques and machinery had successfully reduced the number of workers in the plant from 350 to 300.